|

|

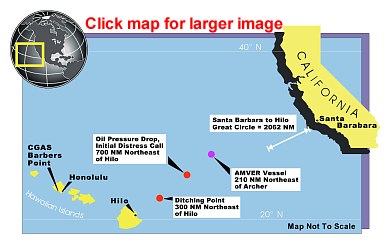

Just minutes after the sun peeked over the horizon, Ray Clamback pushed the throttle forward and the shiny new single-engine Piper Archer III accelerated down the runway at Santa Barbara (California) Municipal Airport (KSBA), lifting off at 6:31 am on the morning of November 20, 1999. Turning to a course of 234 degrees and climbing slowly to 6,000 ft., Ray headed for DINTY intersection, his first checkpoint on the way to Hilo, Hawaii, 2060 nautical miles distant over the blue Pacific Ocean. The extra fuel on board put him right at the allowable 10% over gross weight and it was a slow climb to cruise altitude.

Just minutes after the sun peeked over the horizon, Ray Clamback pushed the throttle forward and the shiny new single-engine Piper Archer III accelerated down the runway at Santa Barbara (California) Municipal Airport (KSBA), lifting off at 6:31 am on the morning of November 20, 1999. Turning to a course of 234 degrees and climbing slowly to 6,000 ft., Ray headed for DINTY intersection, his first checkpoint on the way to Hilo, Hawaii, 2060 nautical miles distant over the blue Pacific Ocean. The extra fuel on board put him right at the allowable 10% over gross weight and it was a slow climb to cruise altitude.

Ray was flying from the right seat, as is his habit on ferry flights. With over 10,000 hours instructing in light aircraft and over 150 ferry flights under his belt, at least 120 across this same route from the U.S. to Australia, the 62-year-old Aussie pilot noted he "is more comfortable flying from the right seat than from the left...and besides, that's where the door is." Accompanying him on this flight was 51-year-old instrument-rated private pilot Dr. Shane Wiley, back flying again after a long hiatus and looking forward to a flying adventure. He didn't know it yet, but he was about to get a bit more adventure than he bargained for.

Ray had picked up the new Archer from the factory in Vero Beach, Florida, just three days earlier, putting 18 hours on the 180-horsepower, four-cylinder Lycoming 0-360 engine during the two-day solo cross-country. Another 2.1 hours were accumulated in a test flight to Los Angeles picking up Shane the day before, after the ferry tanks and temporary autopilot installations and first oil change were completed. The engine still hadn't used a drop of oil.

Passing DINTY, Ray turned a few degrees right to 238 degrees which put him on the great circle track to FITES intersection, off the coast of Hilo. He had programmed the Garmin 430 (GPS) with the flight plan, now it was time to settle back and relax as the Archer droned toward Hilo at a steady 125 knots, about 140 kts. ground speed with a light tailwind. After a while Ray turned over piloting duties to Shane and nodded off.

Shane dutifully monitored the flight's progress on the Garmin's moving-map display, as the auto-pilot maintained heading and altitude, keeping a watchful eye on the engine instruments. Every ten minutes he'd log temperatures and oil pressure. "They didn't vary by even the slightest amount," Shane recalled.

Ten hours into the expected 17-hour flight Shane noticed the oil pressure had dropped, "though it was still in the green, it was quite a bit lower. I shook Ray awake and told him the pressure had dropped, and we were then both very wide awake as he looked at the gauges." Shane remembers then that they "monitored the oil pressure for about fifteen or twenty minutes when the oil pressure dropped again and we knew then we really had a problem." As Ray recalls it, they monitored the oil temperature and considered their options, "and within four to five minutes the pressure dropped again to the bottom of the green. At that point I didn't wait, immediately called guard (emergency) frequency, 121.5 MHz, 'anyone on guard, this is November four one four eight x-ray (the aircraft's registration or "tail" number), I've got decreasing oil pressure and need assistance. I'd like the Coast Guard notified as soon as possible'" and then gave his position--longitude and latitude. "The frequency lit up with replies, which was very reassuring." Ray also had an Iridium satellite phone with him, as back-up, but years of experience had taught him that a call on 121.5 MHz would likely do the job and that was far easier and quicker.

A United Airlines captain flying overhead started the search and rescue wheels in motion, contacting both his UAL base via company radio and FAA Air Traffic Control. ATC notified the Joint Rescue Coordination Center (JRCC) in Honolulu, Hawaii, which coordinates SAR (Search and Rescue) operations for the region, which then notified the U.S. Coast Guard. Ray also asked that his "partner" be notified in Australia of their predicament, passing along their phone number.

Lieutenant Commander Jack Laufer, the search and rescue controller at the JRCC who received the initial call and coordinated the rescue effort recalled later, "at that point, the pilot was very nervous. He was very apprehensive about his ability to stay in the air. He said, 'I can't stay in the air for ten minutes (if the engine quits).' Our first reaction to that information was to find a ship that was close, and have him ditch by it."

After getting off their initial call, Ray and Shane donned their life vests, standard airline-style vests made by Eastern Aero Marine. Ray's two-person life raft was laying on top of the auxiliary fuel bladder, wrapped in bubble wrap for protection during shipping from Australia. "I said to Shane, 'get that bubble wrap off (the raft) and get it prepared.'" Ray also carried a 121.5 EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon, marine equivalent to an ELT). Ray instructed Shane to retrieve it from the back and get it ready. There was a piece of tape securing the EPIRB's string tether and Ray intended Shane to simply get the tether ready for use, "I was just going to hang onto the string from the beacon, if it came to that." Shane, not being told otherwise, tied the tether to the life raft.

Only "about fifteen minutes passed" before United was advising Ray of his options, passing along the information provided to them by the Coast Guard. AMVER (Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Rescue System), a worldwide database of maritime vessels and their location kept for such purposes, provided the latitude and longitude of the nearest shipping vessels able and willing to effect a rescue. As Ray entered the coordinates into the Garmin, other airline captains were already giving him estimated distances of 180 - 200 miles back the way he had come. The Garmin showed the ship 210 nautical miles Northeast, on virtually the reciprocal of his present course.

Ray and Shane and the airline pilots flying overhead discussed their options. They were approximately 700 miles from Hilo. The Coast Guard reported that seas were six feet with winds 25 knots. The water temperature was reported to be 80 degrees F where they were. Shane was concerned that "the water temperatures further north were bound the be colder and that would shorten our survival time in the water." Ray recalls they "figured it would probably drop five to six degrees back to the northeast. I wasn't quite certain what it would be, but I expected it would drop."

With the lowered oil pressure, Ray had reduced his engine speed to 2450 RPM, losing about 10 kts. Turning back the way he came would also mean bucking a headwind. That made the ship just under two hours away, a bit less perhaps because the ship would be steaming directly for him at around 20 kts., give or take a few knots. "A major advantage would be that I would be sure of ditching in daylight." Ray was sure his chances of a successful ditching went down a lot after dark. "The other thing was, there was some doubt that I'd make the 210 miles�and if the (engine) suddenly stopped, I was going to be in the water without anyone knowing precisely where I was."

If they pressed onward towards Hilo, "there was always the possibility that we might well make it there before it died or at least get myself within a hundred and fifty miles of the coast, in range of a Coast Guard helicopter." On the other hand, he might not, which might well mean ditching at night. Balancing that, he would likely be able to rendezvous with a Coast Guard aircraft well before dusk, based on the estimated rendezvous time he'd been given, assuring him of assistance if he did have to ditch after dark.

Shane, recalls arguing against turning back, "I was dead set against going back," but remembers Ray not having a strong opinion either way. As for Ray, he recalled, "we knew things were mounting up against us, but there's not much you can do but make a decision with what you know."

"Most of the airline captains were suggesting that a day ditching, particularly under power, would be far better than a night ditching, and I couldn't help but agree." Ray started his turn northeast. Still, the colder water weighed heavily on Ray's mind, as did the lack of a Coast Guard escort. Shane still pressed for going on towards Hilo, "I really didn't want to go back." As the turn progressed Ray considered, "I thought I'd feel pretty grim if I ended up ditching a perfectly good airplane, though you would never really know, of course." Halfway through the turn, Ray changed his mind and turned back towards Hilo. He was going for it. Ray estimates that about thirty minutes had elapsed since they had first called for help.

As Ray was weighing his options and making up his mind, the Coast Guard was already marshalling its resources and swinging into action. The JRCC issued orders for the "ready" Lockheed C-130 "Hercules" from Coast Guard Air Station Barbers Point on Oahu, Hawaii (west of Honolulu) to be launched. It lifted off at 3:44 p.m, piloted by Lieutenant Commander Matt Reid and co-pilot Lieutenant Junior Grade Beth McNamara who was flying on her first search and rescue mission. Using Ray's position, course and speed passed along by UAL, the navigator computed a rendezvous point and the big old bird, heavy with a full load of fuel, climbed to 21,000 ft. and lumbered northeast at 290 kts to meet up with Ray.

As Ray was weighing his options and making up his mind, the Coast Guard was already marshalling its resources and swinging into action. The JRCC issued orders for the "ready" Lockheed C-130 "Hercules" from Coast Guard Air Station Barbers Point on Oahu, Hawaii (west of Honolulu) to be launched. It lifted off at 3:44 p.m, piloted by Lieutenant Commander Matt Reid and co-pilot Lieutenant Junior Grade Beth McNamara who was flying on her first search and rescue mission. Using Ray's position, course and speed passed along by UAL, the navigator computed a rendezvous point and the big old bird, heavy with a full load of fuel, climbed to 21,000 ft. and lumbered northeast at 290 kts to meet up with Ray.

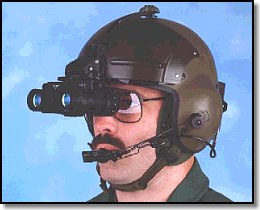

One of the station's Aerospatiale HH-65A "Dolphin" short-range recovery helicopters was also dispatched to Hilo (on the big island of Hawaii) to stand by, putting them as close as possible to Ray. As they waited at Lyman Field, the chopper crew refueled and then settled in, following events over the radio. Any rescue they might make would be after dark and the crew prepared their Night Vision Goggles (which amplify any lights or natural illumination from stars and the moon at night) for use. The Coast Guard Cutter Kiska, a 110-foot patrol boat homeported on the big island of Hawaii was also dispatched. Ray had placed his bet on the Coast Guard and they were doing all he might have expected, and more.

Having made the decision to press on, Ray and Shane discussed ditching procedures and exchanged information on their progress with a succession of three UAL flights, and then an Hawaiian Airlines captain. The Hawaiian pilot also flew light general aviation aircraft and he related having a very similar experience himself with a Lycoming engine. Ray asked him whereabouts that had been and "he said, 'You're not going to believe this, but right about where you are now.'" In his case, he made it safely to shore, which provided some encouragement to Ray and Shane. They also decided that they "were probably dealing with a main bearing problem, though that was little comfort." As the rendezvous time approached, "the oil pressure continued to drop slowly, the oil pressure warning light came on, the oil temperature started to slowly rise and I knew we had a real problem, it wasn't just a faulty gauge," remembers Ray.

A bit after 5:00 the Coast Guard C-130 contacted Ray on the radio, "they asked us to transmit a slow count to ten." After a while they requested another ten-count. Using the Direction Finding (DF) equipment on the Herc, the navigator homed in on the Archer as they descended. At 5:40 p.m. they advised Ray they had him in sight and Ray soon located them "at the one o'clock position about three or four miles away" as they approached at 7,500 ft. "'I was very glad to see them and to know that at least if I�had to ditch in the dark that I'd have a flare path laid for me very quickly." Slowing to the Archer's 115 kt. airspeed would have been difficult for the big Herc, so the pilot proceeded to fly circuits around the Archer, keeping station over Ray as they flew into the setting sun.

A bit after 5:00 the Coast Guard C-130 contacted Ray on the radio, "they asked us to transmit a slow count to ten." After a while they requested another ten-count. Using the Direction Finding (DF) equipment on the Herc, the navigator homed in on the Archer as they descended. At 5:40 p.m. they advised Ray they had him in sight and Ray soon located them "at the one o'clock position about three or four miles away" as they approached at 7,500 ft. "'I was very glad to see them and to know that at least if I�had to ditch in the dark that I'd have a flare path laid for me very quickly." Slowing to the Archer's 115 kt. airspeed would have been difficult for the big Herc, so the pilot proceeded to fly circuits around the Archer, keeping station over Ray as they flew into the setting sun.

Commander Reid gave Ray the latest information on the seas, 8 to 12 ft. and winds 25 kts. Below Ray the cloud tops were at about 5,000 to 5,500 ft. with bases about 4,000 and about 70% sky coverage with intermittent rain squalls. The swells were running east to west, meaning Ray would want to land to the north with a quartering crosswind, parallel to the swells. "They told us exactly what they were going to do if we had to ditch." If the engine quit he would turn north to 350 degrees and the Coast Guard would turn ahead of Ray and lay a line of flares, creating a virtual runway in the water. The Coast Guard reviewed ditching procedures with Ray, "which I knew well because I do fly flying boats. I knew I had to make sure I didn't have the tail down because if it hit tail first it would pitch downward and likely flip over." With the C-130 keeping pace overhead, they settled back into the routine, droning on toward Hilo as the sun set about 6:00. The nearly full moon rose behind them, moonlight reflecting off the clouds, and occasionally, the rough seas below.

At 7:30, 320 miles out of Hilo, "all of a sudden the engine suddenly started to squeal, scream really, like a bearing scream and I knew then that was it." The oil pressure immediately dropped to zero. "I pulled the throttle back, trimmed for a descent�at 75 kts., and turned north. I tried advancing the throttle, but there was no power. I advised the Coast Guard that I was turning north and it was time for them to lay the flares for me." The "C-130 turned north in front of us and told me to hold a heading of 350, that was how he was going to lay the flares."

"You could hear in his voice ... he was very nervous," said Reid. "He said, 'Hey guys, it doesn't look like it's going to make it.' right when his engine failed."

Having completed the steep diving turn to a heading of 350 degrees, in the back of the Herc crewmen began dropping a string of Mark 25 and Mark 58 flares, which burn yellow for up to 60 minutes, from the plane's flare launching system. They also dropped a datum marker buoy, which transmits a radio signal to mark the approximate location of where the Piper was ditching.

Having completed the steep diving turn to a heading of 350 degrees, in the back of the Herc crewmen began dropping a string of Mark 25 and Mark 58 flares, which burn yellow for up to 60 minutes, from the plane's flare launching system. They also dropped a datum marker buoy, which transmits a radio signal to mark the approximate location of where the Piper was ditching.

Suddenly, as Ray descended through about 5,000 ft. in the clouds "there was an incredibly loud bang--and everything went black." Somehow, the engine's death throes took out the electrical system. "He radioed and we could hear banging in the background," McNamara said. "He was talking really fast. He said, 'I think it's going to quit on me.' It was an intense situation. A few seconds later we heard no noise in the background. We knew he was just a glider at that point. We knew he was going into the water, and that is not a good thing."

"There was smoke coming in from my side, under the panel. I figured it must have thrown a rod through the case on that side," remembers Shane. "I held a torch (flashlight) on the panel for Ray and the instruments were starting to go, I knew we had only a few minutes left to get in the clear." Murphy had definitely made his presence known. Ray concentrated on the instruments, not even recalling the smoke in the cockpit, "Ray was concentrating 100% on what he was doing, I was taking care of mine," noted Shane.

At 4,000 ft. they emerged from the clouds, just in time as Ray felt, "I was starting to lose control--the instruments were winding down, the AH (artificial horizon) was laying over." It was "very dark, the clouds obliterated the moon, the only lights were from the flares, I had no landing light." With the flares close ahead, Ray realized he was too high and would overshoot the landing zone. Ray recalls, "I made a couple 'S' turns to lose altitude before over-running the flares."

As they descended silently, Ray pulled both tabs on his life vest, inflating both chambers, "I had considered this carefully and we'd discussed and debated it many times over the years. I'd decided that in a low-wing aircraft I'd inflate the vest inside. Plus, I wasn't too sure about them, mind you I had no reason to question, but I carried more than one set just in case. If these didn't work, I wanted to be able to use the others." Seeing Ray inflate his vest, Shane did likewise, but "I pulled only one tab on my vest. I was not happy that Ray had pulled both tabs, there was only one door and he was by it."

Ray instructed Shane to turn on the EPIRB and recalls the LED was illuminated, indicating it was working. At about 1,000 ft. Ray reached over and opened the Archer's single door to his right, leaving it open in the slipstream. While Ray doesn't remember it, Shane is positive, "I stuck something, just grabbed something, in the door" to keep it from closing. Shane recalls pulling hard on his seat belt "until it felt like it was cutting me in half. I knew that if I was injured, that was it, I had to do everything I could to stay in good shape."

Ray's experience flying Lake amphibians and hundreds of lights-out night landings with students stood him in good stead, "I was used to getting a reference only off the runway lights�probably done it myself five hundred times at least." As he approached the water he had only the flares to guide him, the moon was obscured by the clouds, it was pitch black. "I knew I had to get close to the flares to gauge when to flare the airplane, they were my only reference." Though the flares had to have been moving up and down as a result of the swells, Ray noted he "didn't notice any movement, probably because there were no other references."

Flying from the right seat, Ray chose to land to the right of the flares, "it is easier to look out the windscreen to the left and straight ahead than out the side to the right, it gave me a good sight picture over the nose. I knew from my sea plane experience that I wanted to be as level as possible, I really did want to get the three feet (landing gear) into the water at the same time, I reckoned that was my best chance of staying upright�I had avoid a tail low landing at all costs, that would be a disaster." Flaring the Archer, Ray "set it level as I could tell, I would have thought I was less than a hundred feet away from the flare path. I had no idea when it was going to (impact the water), but I knew I was about the right height." Ray succeeded in his execution of the ditching and the fixed main and nose gear hit the water at the same time. Ray recalls, "it stopped very quickly, of course. It was Splash--Bang! It stopped very rapidly." Shane described it as, "there was a big thump, that was it. We stopped immediately, the deceleration was incredible!" The "S" turns worked, just. They impacted the water beside the next to last flare.

Flying from the right seat, Ray chose to land to the right of the flares, "it is easier to look out the windscreen to the left and straight ahead than out the side to the right, it gave me a good sight picture over the nose. I knew from my sea plane experience that I wanted to be as level as possible, I really did want to get the three feet (landing gear) into the water at the same time, I reckoned that was my best chance of staying upright�I had avoid a tail low landing at all costs, that would be a disaster." Flaring the Archer, Ray "set it level as I could tell, I would have thought I was less than a hundred feet away from the flare path. I had no idea when it was going to (impact the water), but I knew I was about the right height." Ray succeeded in his execution of the ditching and the fixed main and nose gear hit the water at the same time. Ray recalls, "it stopped very quickly, of course. It was Splash--Bang! It stopped very rapidly." Shane described it as, "there was a big thump, that was it. We stopped immediately, the deceleration was incredible!" The "S" turns worked, just. They impacted the water beside the next to last flare.

Ray recalls the Archer was now "sitting just as if it was on the ramp. I got out of the airplane reasonably quickly, the wing was nine or ten inches out of the water, my feet hadn't got wet at that stage. I was standing on the wing, without holding onto anything." Shane quickly followed, then turned around and reached back in for the raft, with the EPIRB attached. Shane handed the raft to Ray. "I threw the life raft forward (of the wing), I reasoned the back end of the Piper wing has rather sharp edges. I threw it forward believing that the thing was going to inflate when I'd give it a mighty old tug and then I'd pull it over along side the airplane and just step in, I would never even wet my feet." Ray gave the tether "a mighty old tug, but nothing happened!" Before Ray could consider his next course of action, the Archer started to nose over. Shane yelled to Ray, "'the tails coming up, we better clear out!' I knew if we didn't do something it (the tail) could hit us if we stayed where we were."

Ray shouted to Shane to jump off the rear of the wing as he followed suit, "I followed Shane into the water off the back as well," still holding onto the life raft tether. "I was very concerned that we didn't get hit by the tail as the plane went under," thus the decision to jump aft into the water. As the Archer started to go under, the tether was ripped from his hand. Ray surmises that the raft caught on the wing as it submerged. "That was a black moment, I've got to tell you," remembers Ray. As the pair watched, the Archer disappeared beneath the surface, it had been no more than three minutes by Ray's reckoning. Shane felt "an immense and total relief. I had survived the crash, I had no injuries, the water was not too cold, I had a life jacket that seemed to be holding me up. It wasn't until much later that the full significance of losing the raft hit me."

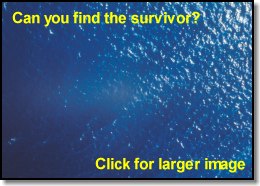

As this all transpired, the C-130 crew was trying desperately to locate the downed airmen. When the electrical system failed, the lights went out and they lost track of the Archer as it penetrated the clouds and a rain squall. They had no idea if the ditching was successful or not. In the coal black night the C-130 navigator set up a search pattern with the survivor's approximate last known position in the center and they began a search.

While Shane never saw the life raft again, "I thought is just sank," Ray remembers seeing the raft bob to the surface, still uninflated, but "it was too far away" and was being carried swiftly further away by the winds. "I didn't realize at the time, in the heat of the moment, that the Coast Guard had lost sight of us. I was confident that they would soon be back. It wasn't a problem, we should have a life raft pretty quick. I had spoken to them, both a man and a women on the plane, and told them we had only a two man life raft and we're two big men, and it would be a pretty uncomfortable night if we had to spend it in that small raft. He had told us "not to worry, I can drop you a string of three (the Coast Guard's air droppable life rafts are dropped three at a time spaced out along an 800 ft. lifeline) as soon as we locate your raft after you egress the airplane."

As the raft was carried away by the wind and current Ray noted that the EPIRB was still attached and he "could see that the green light on the beacon was lit," so he figured that the searchers in the C-130 would at least have that signal to guide them into the area. Unbeknownst to Ray, the EPRIB was not transmitting, even though the light was on. The C-130 had nothing to home in on.

In the water, the survivors were dealing as best they could with a bad situation that became bleaker "as I saw them (the Coast Guard C-130) flying their search pattern I realized then that they must have lost track of us when we ditched and couldn't find us." No matter which way they turned, they were pummeled by the waves. The only light was from the single dim locator light on each vest and Shane's small AAA-cell Mini-Maglite. They could see the lights of the C-130 flying its square search pattern and Shane tried signaling the Herc with the small flashlight, but the lights were too dim for the C-130 crew to make out.

Darkness, scattered rain, large seas and white caps made for a most difficult search. Two hours passed as the crew searched in vain for the survivors. With no lights visible below and the rain squall continuing to obscure their view, the C-130's crew could only occasionally see the line of flares they'd dropped, until they burned out, and nothing else. By 9:30 p.m. the Herc was running low on fuel. Reluctantly, Reid turned his aircraft towards Air Station Barbers Point, leaving the Australians alone in their struggle against the seas. "It was an extremely difficult decision," remembered Reid.

Ray recalls that, "on their last run they flew right at us, then they pulled away not two or three hundred yards before us, though it could have been half a mile for all I could tell," and then they were gone. "They made a right hand turn and away they went toward Honolulu." Shane watched the lights disappear and Ray remembers him asking, "will they be back?" Ray reassured him, telling Shane, "I can guarantee you they'll be back. They'll search for two days before they give the search up." Indeed, as the Herc departed, they dropped another datum marker buoy for the next crew to home in on and use as a search datum. Ray recalls feeling pretty depressed when the C-130 disappeared, "I was not very happy to see it go."

Both survivors were swallowing a good deal of salt water, there was just no escaping it. "No matter what way you faced, you couldn't help but swallow the sea water. Shane kept trying to turn himself around to avoid the water," but was having little success, "even if you faced away from the waves, the water broke over your head and engulfed your mouth." Ray couldn't make out the waves in the darkness, so didn't try to reposition himself. However, he "treaded water in an attempt to raise my head higher out of the water and not swallow so much." He felt his pants were dragging him down and eventually took them off. They disappeared, taking with them the $3500 U.S. and $1000 Australian Ray had in his pockets.

Shane noted that he was quite a bit thinner than Ray, "he had quite a bit more fat on board, so he had more buoyancy, so he took a different tact than me. I really tried to avoid the water, working at it, he seemed to just ride it out, treading water, there we are, just different approaches."

Ray complained that his stomach wasn't doing so well, the salt water he couldn't help but swallow was taking its toll. "It was lucky that he (Shane) was a doctor, he said I should induce vomiting to empty the sea water from my stomach" and Shane demonstrated the technique by sticking two fingers down his throat. Ray did it himself and "it was an enormous relief, I immediately felt better. Each time I did it I felt better right away." The night dragged on. Ray remembers that they had no difficulty staying together, despite the waves and wind. "We never did look at the time," Ray recalls.

They talked on and off, induced vomiting regularly, Shane remembers doing it about a half dozen times during the night, and waited patiently. Shane noted, however, that "it was harder to vomit every time I did it, as the night passed." The clouds and rain passed and the moon lit up the sea. The salt water was taking its toll on Ray's eyes, he was having difficulty seeing. While they didn't realize it at the time, hypothermia and dehydration were also affecting both their faculties. "Even though the water was warm, we spent a very uncomfortable night, I can tell you," Ray remembers.

Shane remembers that "no matter how I turned, it seemed the water came at me." While the pilots couldn't see the little locator lights on their vests, Shane thought they were very bright, "I thought you could read a book by the light from those little little lights."

As the unsuccessful search crew turned for base, back at Barber's Point the duty officer started making calls to round up off-duty crew to send out another C-130. On a Saturday night staffing at the air station was at minimums and many possible crewmembers were out of touch, otherwise engaged. By 10:00 p.m. the crew was assembled and readying for the mission. In Flight Planning, Captain Roger Whorton, the air station commander and the pilot for the second C-130 sortie, and Lieutenant Commander Douglas Olson, his co-pilot on this mission, debated whether to take along Night Vision Goggles (NVGs). The Coast Guard's C-130 crews aren't trained in their use and as a crewman tried to brief them on the NVGs' operation it became obvious that it wasn't going to be enough--they decided they'd have to rely on what nature provided.

As the unsuccessful search crew turned for base, back at Barber's Point the duty officer started making calls to round up off-duty crew to send out another C-130. On a Saturday night staffing at the air station was at minimums and many possible crewmembers were out of touch, otherwise engaged. By 10:00 p.m. the crew was assembled and readying for the mission. In Flight Planning, Captain Roger Whorton, the air station commander and the pilot for the second C-130 sortie, and Lieutenant Commander Douglas Olson, his co-pilot on this mission, debated whether to take along Night Vision Goggles (NVGs). The Coast Guard's C-130 crews aren't trained in their use and as a crewman tried to brief them on the NVGs' operation it became obvious that it wasn't going to be enough--they decided they'd have to rely on what nature provided.

On the ramp, the Dolphin helicopter that had deployed to Hilo landed. The crew had been recalled when it was obvious they wouldn't be needed as the ditching was well beyond the chopper's mission range. As the C-130 crew started the four Allison turboprops, the pilot of the helicopter ran up to the door. Offering up a set of NVGs, he suggested they take them. Whorton and Olson looked at one another, shrugged and Whorton said "okay, take 'em." Not really expecting a positive response, over the intercom Olson inquired of the crew, "anybody here know how to use NVGs?" Petty Officer Shane Reese, a scanner in the rear of the aircraft, piped up. He'd formerly been in the Army and had used NVGs before; not this exact model, but he understood how they functioned and could make them work. At 10:30 p.m. the Herc rolled down the runway and lifted off into the bright moonlit night.

Homing in on the datum marker beacon, the C-130 arrived on-scene and began its search at 1,000 ft., slowing to 135 kts. All the exterior lights were turned off, they would interfere with the NVGs. The survivors could hear the big turboprop, but they could see little or nothing, despite the bright moon. The crew set up a sector search patter centered on the datum. On only the third pass there was a loud whoop from the scanner as Reese saw two faint lights through the NVGs about two miles away. It was 12:45 p.m. The C-130 dropped a Mk.-58 flare southwest of the lights, to serve as a new datum marker.

The bright moonlight now became a hindrance, drowning out the small, dim locator lights, even with the NVGs. Whorton flew back and forth past the lights, time and again, from different angles and at different altitudes, in an attempt to get a better view. In the choppy water it was impossible to identify the source of the lights. Olson recalls, "we knew the lights shouldn't be there, so we had to assume they were from the ditching, but with no response we weren't at all sure it was survivors, it might have just been wreckage or empty life vests." After the excitement of finding the lights, failure to make a positive ID dashed the crew's hopes, but they continued their efforts.

In the water, Ray's and Shane's spirits were buoyed by the sight of the Coast Guard plane overhead. "They flew over and immediately made a right hand turn and then a hard left back past us and then they kept fly around and over us, always keeping us on their left, over and over and over, so I knew they had discovered us." After the flare was dropped, Ray noted "Shane wanted to swim to the flare thinking they had dropped a life raft, but I said I reckon they were getting wind drift and they wouldn't be dropping life rafts willy-nilly, they could just as easily drop them on us and kill us." Shane remembers actually starting to swim towards the flare to see if they'd dropped a raft, but then " Ray was getting very distressed, so I had to come back."

"Ray was very concerned he wouldn't survive if we were separated," recalled Shane, "about this time he (Ray) was starting to ruminate about not lasting much longer. Ray wanted to hold onto me and I didn't want him to hold onto to me."As the crew tried to make out what, exactly, was below floating in the water, the lights would spread apart, sometime by as much as 150 ft. and then come closer together. There was no pattern, they couldn't see any signaling, nothing to tell them that Ray and Shane were down there waiting to be rescued. Shane had removed the light from its keeper on both his vest and Ray's, "and every time they came to pass over us I would pull Ray towards me, he was quite fatigued by then...I'd grab his light and I'd have his light in one hand and mine in the other and I'd lift them up in the air as high as I could." However, this was apparently not recognizable as a signal to Reese up in the Herc.

Figuring any survivors would try to stay together, this further dimmed the crew's hopes and without a positive ID, they wouldn't be air dropping a life raft. At times they flew as low as 200 ft. above the water, but the light sources remained a mystery. Without the NVGs the lights were impossible to see at all, even though the crew knew exactly where to look.

Reese noted, "Without the night-vision goggles, it would have been impossible to see (the lights). We thought they were the plane's wing-tip lights. We went down as low as we could, but we still couldn't tell what we were looking at. Even flying in the daytime, seeing a person in the water is hard. We thought if it was a person, they'd be waiving the lights, but they looked like they weren't moving."

Meanwhile, based on the initial sighting, the Coast Guard had contacted an AMVER vessel. The Nyon, a 743-foot bulk carrier on its way from New Orleans to Inchon, South Korea, was 70 miles away from the ditching site when it received the AMVER request from the Coast Guard. The Nyon changed course and headed towards the survivors at top speed. The crew dropped three flares and another datum marker buoy, and circled until the Nyon got on scene

As the Nyon came over the horizon, she appeared on the C-130's radar and Whorton turned towards the big ship. They flew low over the ship to get their attention and to confirm if it was the Nyon. Coming up on marine channel 16, the ship's captain confirmed it was, indeed, the Nyon. Olson reiterated that they had two lights in the water with possible survivors. The Nyon's captain assured them he was proceeding at best possible speed.

The Nyon arrived on scene at 3:15 a.m. By now the moon had set, it was pitch black again. Surveying the situation, the captain considered it too risky to launch a small boat into the night in those waves. Taking up a position next to the marker buoy southwest of the lights, he would wait a couple hours until dawn.

The C-130 resumed their search, not at all satisfied they had identified survivors. The crew had discussed dropping a life raft by the two lights, but decided to wait. If the survivors weren't by the two lights, they risked not having a raft to drop to the men if they spotted them later in a different location.

Shane glimpsed the Nyon's lights as she hove to next to the buoy and shouted to Ray. At first Ray thought Shane must be seeing things, but then as he crested a wave, he too saw the boat's lights against the night sky, "though I had no idea how far away it was." Shane told Ray he was going to swim for it. Ray cautioned him, "we ought to take is steady as she goes, we don't know what's over there, it could be nothing, we don't want to waste energy, but at that point he decided he was going to go." Shane, indeed, wasn't feeling at all cautious, "I wasn't sure what it was, but it was something and I swam towards it. Then I saw the black outline of the ship (against the sky) with some lights above it and I thought it might just be some navigation warning lights on an old shipwreck on a reef or something. As I swam closer I could hear the waves really pounding up against it. There weren't many lights, it was dark except for those few lights and I thought 'this really is a reef.' I was concerned that as I got closer I'd be pounded to death by the waves. But, as I got closer I was sure it was a ship. I swam around to the other side looking for a ladder or someplace where I could get on." knew that was my chance for rescue and I just swam for all I was worth." Shane quickly outdistanced Ray while Ray took it easy, making slow but steady progress towards the ship.

Shane was at the stern of the ship and couldn't see if there was anyone on deck or not, most of the lights were out, "the ship was dark, it looked like everyone was asleep." Shane noted he was "very tired" but, finally he saw what he thought was some movement on the ship and he started yelling, "I shouted 'help'" and got no response for a while so "I had no idea if they heard me. It looked like people might be gathering and that they might be looking in my general direction, but the ship was still dark, there were no light, no searchlight, no flashlight. I finally came to the conclusion that there was really nobody there, that it was my imagination, and I stopped shouting and started to turn away " to swim back to Ray. Then, finally, "all the lights came on." A searchlight was shown down on Shane and the ship itself started motoring in reverse towards him. "I was elated," Shane recalls, "I;d made it!"

The Nyon's captain notified the C-130 that the crew had heard shouts and had identified at least one survivor that they were preparing to bring him aboard. Spirits in the Herc immediately soared.

Nyon crewmembers threw down a life ring on a rope. Shane swam towards it and grabbed it. They then pulled him towards a gangplank that was let down on the side. "The problem was that one second the sea was up at the gangplank and then the next second it was four meters (approximately 13 feet) in the air. I thought, this is not a good idea and finally got that across" In the end, Shane was hauled up the side of the ship, "I had about a half-dozen ropes by then, I was afraid they'd drop me, I had one wrapped around my waist and another around my chest, and they just pulled me up."

Having lost track of Shane, Ray had no idea he had been rescued, he was concentrating now on getting himself to the ship. Ray had spied lights lower down, closer to the water, at the side of the ship, and swam slowly towards them. Approaching the ship "I could then see the lights were coming from a large hole in the side of the ship." Ray finally arrived at the ship, "about ten minutes after Shane," he reckons, but it was likely longer.

As he neared the opening he spied crewmembers there, urging him forward. Every time he tried to swim to the large hole, the huge waves pushed him back. "I would swim ten feet forward and the waves would push me eight feet back." The crew threw him a line, but they just missed. "It was only just out of reach, but it might as well have been a a kilometer." Ray was weak after the long ordeal, hypothermic, dehydrated, was having difficulty seeing, and was rapidly running out of what little energy reserves he had left.

While the crew was Croatian, they spoke English. They exhorted him to try harder, "They were yelling to me to swim harder," but he was already giving it his all. Finally, on the fourth try, they hit their mark with the line and he grabbed on tight. He was pulled closer, they dropped him a life buoy, "'hang on' they yelled" recalls Ray, "and I held on for all I was worth and they pulled me aboard." Ray collapsed, "I had no idea of the time or anything." It had taken nearly an hour to get him aboard. It was 4:50 a.m., just over nine hours since they ditched. The captain notified the Coast Guard that they had both survivors onboard and a very happy crew headed back to Barbers Point. The Coast Guard called Australia immediately, advising them of the successful rescue, a tremendous relief to all of them waiting nervously.

The next thing Ray remembers he was in the ship's infirmary being tended to. The Nyon was a new ship, commissioned in August of that year, and was complete with a well-equipped infirmary and a trained paramedic. Placing Ray in a cradle, they gently hosed him down with warm water for 30 minutes to raise his body temperature back to normal. Then they put Ray in bed and a paramedic sat by him, giving him warm tea and broth. Ray was so weak he could not sit up. They treated and covered his swollen eyes and tended his cuts and abrasions. The abrasions in his groin and on his legs were likely from the pants rubbing as he treaded water, plus he had abrasions on his neck from the vest. The cuts, Ray surmises, came from when he was pulled aboard. "Ray looked pretty bad. He wouldn't have lasted until daylight," recalled Shane, someone with the medical experience to make such a judgement.

Shane was in generally better shape physically, though still mildly hypothermic and dehydrated. Shane's neck was rubbed raw by the life vest from his constant turning while attempting to avoid swallowing seawater.

As Ray and Shane were warmed up and treated, the Nyon got under way to rendezvous with the Cutter Kiska outbound from Hilo. Ray was still so weak five hours later that they had to transfer him to the Cutter on a stretcher with a towel over his eyes to protect them from the bright sun. With the rough seas, the transfer of the two survivors took almost an hour. The Kiska then turned back to Hilo, proceeding at a modest pace to conserve fuel. They had raced out at full speed, 26 kts., in only eleven hours. The return would take twenty, time enough for Ray to gain the strength to stand on his own. Arriving in Hilo, both survivors walked off the cutter unassisted, though it would be a week before Ray was back to himself again and Ray remembers "my leg muscles were sore for three weeks from treading water that night."

This ditching incident should help hammer home some critically important points to pilots.

Ray emphasized that "the thing that got me out of this was calling up the Coast Guard immediately. A lot of pilots are reluctant to do that because it could have been just a gauge� There was no hesitation on my part, as soon as I saw that oil pressure drop I decided it was time to call the Coast Guard in. That was a wise decision." Indeed it was. I can't put it any better.

It is far better, in such circumstances, to call out the cavalry and then have to cancel because it was a false alarm than to put off calling while you investigate and decide if it's a real emergency or not. The sooner you can get assistance, the easier everything becomes. The sooner the SAR wheels are put in motion, the sooner they will get to you.

Look at all the assistance and advice Ray was able to tap into by making his call for help right away. That information allowed him to consider all the available options, most of which he'd not have known about, and make a decision that ensured help would arrive in a timely fashion. Don't be reluctant to make the call immediately that you believe you may be in trouble. Nobody in the emergency response business is ever going to get upset about that, even if you end up canceling later on.

Ray figures his successful ditching was "80% luck, 15% experience, and the remaining, (his) flying skills." I'm inclined to give his experience and flying skills far greater weight, more on the order of 50%. Disregarding all else, his years of night landing instruction with lights out was likely a large part of the reason that the ditching came off as well as it did. That's a lesson for all pilots, not just those who fly over water at night. When was the last time you practiced a lights out night landing?

The attitude at which you impact the water can significantly affect how the aircraft behaves. His experience enabled him to flare at the correct height with only the flares for reference and to maintain that attitude until impact. His experience flying Lake amphibians had to also be a big advantage. Again, attitude when landing an amphibian is critical.

Ray's nighttime ditching, in far less than the most favorable conditions, went textbook perfect. Despite all that was working against him, including loss of electrical power fairly nasty seas, he pulled it off perfectly. The flare path laid by the C-130 was, without a doubt, a big factor in how well it went. Nevertheless, I suspect it would have worked out okay even without that assistance. Ray did all the right things setting up the aircraft correctly for a ditching.

Both survivors inflated their life vests while still in the air. Ray commented that over the years he'd been involved in many discussions and debates about when to inflate the vests and he'd decided that in a low-wing aircraft he'd do it inside, but in a high-wing aircraft he'd wait until exiting. I cannot disagree too strongly with his decision to inflate the vests inside the aircraft. Stuff happens, even under the best circumstances things can go wrong. Having experimented in Survival Systems Training Inc.'s METS dunker, I can assure you that you don't want to have your vest inflated should the aircraft become immersed before you egress, even if it doesn't flip over. Should it flip, you'll be in more difficult straits. It won't necessarily trap you inside, but it very easily could. If submerged, at best it will significantly slow your egress, I guarantee it. If you end up needing to use an alternate exit under water, you'd be in even bigger trouble.

Even if the plane is floating, should you have to exit via a window or baggage door, it could impede your getting through the smaller opening, possibly damaging the vest in the process. The inflated vest also makes if much harder to move around inside the cramped confines of a typical light plane cabin and to get out, even under the best circumstances. You don't want anything to slow your egress. I cannot think of a single good reason to inflate the vest before you exit the aircraft, not a one.

Ray also commented, "I was always confident of getting on the water with the airplane being in one piece, not broken up, so I had no reason to prop the door open." Feeling confident of your skills is one thing, and a useful survival trait, but being over-confident or assuming a successful outcome for something like a ditching, even more so at night, is potentially deadly. While the slipstream might keep the door ajar while in the air, a bad bounce on impact with the water, or nosing in, might easily have closed the door and it could then become jammed. Shane recalls jamming something into the door to ensure it stayed open, a far better plan of action. Take the precaution of sticking something in there to prevent the door from inadvertently closing. Some doors mechanisms will also prevent closure if the handle is moved into the locked position while open. Check your aircraft's door so you know how it works.

Ray commented that "I knew I had to make sure I didn't have the tail down because if it hit tail first it would pitch downward and likely flip over." While hitting the water first with the tail wouldn't be ideal, there's no data to suggest that this would necessarily cause the aircraft to flip. If you look at the dynamics involved, it would likely cause a more dramatic and forceful impact with the water as the remainder of the fuselage smacks the water due to the rapid deceleration at the aft end, but a flip is unlikely. In fact, the existing data suggests that flips are rare and the successful egress rate so high that it likely has little impact on survival rates in any case. (See ditching links below)

By the same token, keeping the nose out of the water as long as possible helps ensure you stay sunny side up. The ideal attitude to impact the water is with the nose slightly high. You want to be careful not to stall into the water since the nose will drop at the stall. What you are trying to avoid at all costs is the nose impacting first and thereby digging into the water. The dynamics of such a nose first impact suggest that this could, indeed, cause a flip, but not necessarily so, depending on other factors.

The failure of his life raft made a difficult situation much, much worse. The life raft Ray brought along was manufactured by American Safety, a company defunct for 12 years at the time he ditched. Ray believes it was 27 months since it had last been repacked and certified. Even using a two-year repack interval, the legal requirement in Australia, it was past due for a service had it been a commercial operation. He noted that when they called the companies they now use for servicing their life rafts, they declined to do so because they didn't have the manuals. It's entirely possible whomever serviced it last didn't have them as well, but perhaps weren't as forthright or knowledgeable enough to care or know. Problems tend to get worse as a raft ages, especially so if it has had less than the very best care. At no less than 12 years old, probably older, the raft could have been at or near the end of its useful life and should have been serviced annually.

There are many possible failure modes that can cause a life raft to not inflate. The most obvious one is that the gas leaks out of the cylinder. This is actually something that any owner can check for himself with an accurate scale. If you weigh the raft when you first get it to get an accurate data point, any significant loss of weight, a quarter pound or more, is likely the result of gas loss--time to take it in to be serviced, or at least to be checked by someone knowledgeable. If there's no gas in the cylinder, all the yanking in the world isn't going to make any difference. That doesn't necessarily mean you're sunk, you can always open up the raft and use its attached manual inflation pump to inflate it. It can take a while, but in warmer waters this wouldn't be a big problem.

Another common failure point is the firing head. If this jams, it won't allow any gas into the raft. Firing heads are mechanical mechanisms and like all such have myriad failure modes. While designed for the most part to be pretty reliable, stuff happens. One common source of problems is corrosion. This is one of the reasons it pays to store the raft where it isn't subject to environmental extremes. It's also a why regular servicing is so important as corrosion tends to build-up over time.

It's also possible to improperly pack the raft so that the inflation line gets hung up, and rafts tend to be very sensitive to how they are packed, even a minor error in routing the line or folding the material can cause problems. Sometimes a few extra, hard yanks on the inflation line will do the trick. Sometimes it takes more than a hard yank. In one raft test I conducted, an EAM raft, freshly serviced by the manufacturer, didn't inflate, despite yanking hard a number of times. I finally inflated it by putting both feet on the raft, either side of where the line went inside, and pulling with all my strength. If all else fails, you can open up the raft and sometimes operate the firing head manually at the firing head, there's usually an obvious cable or pin to be pulled. This is also the solution when you yank and the line comes loose from the raft, and yes, it has happened. More often than not, failures to inflate can be traced to long service intervals or improper servicing.

Ray made an error when he jumped off the back of the wing with the raft floating forward of the wing. On the other hand, it could just as easily have not become a problem if only chance hadn't caused the raft to catch on the wing, ripping the tether out of his hand--hindsight is 20/20. Still, was it really necessary to avoid deploying the raft aft of the wing in the first place. The answer is "no." Unless there was obvious damage and torn metal, the edges of the flaps posed no real danger to the raft. Aviation raft material is pretty tough stuff and while you don't want to abuse it unnecessarily or impose very sharp edges upon it, any edge that wouldn't easily cut you would not likely hurt the raft by just rubbing against it.

But, even after they lost the raft, all was hardly lost. If that tiny, uninflated two-person raft was visible on a pitch black night lit only by the flares some distance away, it could not have been all that far from the survivors. By Ray's account it was drifting away, not being driven by high winds at high speed. I'm not so sure I wouldn't have deflated my vest and swum like mad to get the raft back, especially since the emergency beacon was also attached to it. You could also argue that it would be foolish to allow yourself to risk being separated from your companion survivor. Sometimes there are no easy choices.

An emergency beacon is the most effective way to ensure you are rescued promptly (especially if it is a 406 MHz unit, which I strongly recommend). Ray carried a nearly new, full-size floating 121.5 EPIRB with him. Next time he'll likely be much more explicit giving a co-pilot instructions for dealing with the beacon in preparation for a ditching. However, the best time to take care of any such instructions is before leaving the ground, not under the stress of dealing with the emergency. A pre-takeoff safety briefing is as sensible a precaution for general aviation flying as it is for the airlines, where it is required by regulation for good reason. It makes even better sense when flying over water. Dealing with a ditching is generally more complicated than a normal off-airport landing.

The life raft was still wrapped in its protective bubble wrap from when it had been shipped to the U.S., an indication that Ray hadn't really prepared fully for the possibility of a ditching. Any equipment you're likely to need in an emergency should be ready to go, you often don't have the luxury of time that Ray and Shane had.

Ray also owns a GME Electrophone MT310 Personal Locator Beacon (121.5 MHz) that he left at home in Australia. I don't think he'll ever do that again. A working emergency beacon would have saved them a great deal of anguish and suffering.

Ray also owns a GME Electrophone MT310 Personal Locator Beacon (121.5 MHz) that he left at home in Australia. I don't think he'll ever do that again. A working emergency beacon would have saved them a great deal of anguish and suffering.

Ray believes that Shane turned on the EPIRB, and Shane is positive he did so, that the green LED indicating activation was lit. Or, was that the test mode? Some EPIRBs include a strobe that would have been flashing once it was activated, but neither Ray nor Aminta was able to provide any information on exactly what model EPIRB it was. We'll never know for sure, but it wouldn't be the first time that mix-up had occurred. Just a reminder to make sure to read and understand the operating instructions for your equipment. Doing it before you need it ensures you have no distractions, so you are less likely to miss anything important. In any case, the Coast Guard never received the EPIRB's signal. Even if it was properly activated, it is entirely possible it failed to work.

Electronic equipment is always subject to failure, even emergency beacons. While it is possible that this was just an untimely failure, my experience is that if it did fail, it was probably faulty from the get go. One of the few advantages of a 121.5 beacon is that it is so easy to test. Just tune the VHF radio in the aircraft to 121.5 MHz and turn on the beacon (during the approved test period, the first 5 minutes after any hour). If it is functioning, you will immediately hear the distinctive sound of the beacon. According to Ray, nobody ever checked that beacon after it was purchased. It is always a good idea to check the operation of any emergency equipment you buy, especially electronic equipment, before the need to use it arises (sealed units like flares being the exception).

Ray carried a handheld Iridium satellite phone (a very expensive gadget) in the Archer, as a back-up communications device. Yet, he did not have it in a waterproof pouch. When asked, Ray commented, "I never thought to do that, would have been a good idea...but I never expected to have to ditch either." Even the crude and unreliable protection of double bagging it in zipper-lock plastic bags might have sufficed for at least temporary use. A proper waterproof pouch would have cost a trivial amount (especially compared to the cost of the sat-phone) for the added utility and security it would provide in a survival situation.

If the Iridium phone had been so protected and he had taken it from the aircraft when they egressed, then they would have been able to communicate and assure SAR that they were there and alive. While it would take a little while to make the connections, they could have also provided vectors for the C-130 overhead, enabling them to locate their position and drop them a life raft.

Likewise, if Ray had carried an aviation handheld VHF transceiver in a waterproof pouch, or a waterproof marine handheld VHF radio, he could have communicated directly with the SAR crews. Either via vectors he provided or use of their DF equipment, they would have quickly located them in the water.

Shortly after his ditching and survival experience, Ray visited Corporate Air Parts in Van Nuys, California and purchased a Switlik Helicopter Crew Vest that is equipped with two large pockets to hold survival equipment. A vest just like the one his partner Aminta Hennessy always wears on ferry flights, but which Ray previously felt was too much bother, too heavy and too uncomfortable. "If I'd had a couple flares with me, they could have found us right away," Ray declared, "I hate admitting it, but I reckon she was right (to wear the Switlik vest)."

The choice of the Switlik Helicopter Crew Vest is an excellent one, though there are other good options as well. Check the links below for more on life vest options and a list of what I carry in my own Switlik vest.

Ray admits, "I never expected anything like this to happen. I'd been doing this for so long that I suppose I became complacent." His complacency certainly contributed to his problems after the ditching. Call it whatever you want, complacency or denial of the risk. It can happen to you! No amount of experience or hours or preventive maintenance is insurance against something going wrong. Complacency is insidious. Complacency is one of the more difficult things a pilot must combat, especially a high time pilot or one doing the same task or trip over and over.

There is no substitute for having signaling and survival gear on your person when it comes time to abandon your plane or boat. Only the equipment you carry on your person can be counted upon to be available when you really need it. Commander Olson noted, "a big, bright flashlight or some flares would have made all the difference in finding them."

There is no substitute for having signaling and survival gear on your person when it comes time to abandon your plane or boat. Only the equipment you carry on your person can be counted upon to be available when you really need it. Commander Olson noted, "a big, bright flashlight or some flares would have made all the difference in finding them."

They didn't even have a signal mirror, the most basic signaling device that easily fits in a pocket, though the wallet Ray lost when he discarded his pants did hold credit cards. The hologram used as a security device on the cards has been successfully used as an improvised signal mirror in at least one SAR case. It should also be noted that with the bright moonlight that was present that night, once the rain had passed, even a simple signal mirror would likely have proved effective. With a bright moon, a conventional, high quality signal mirror is visible for 2-5 miles

This incident should also drive home the message that the small locator lights on aviation life vests are designed to allow survivors and crew to locate one another, not necessarily for SAR to find you. If you are intent upon using them as a signal, for whatever reason, remember to move them about, waving so they are more likely to be noticed. Just holding them up, as Shane did, isn't enough.

Shane finally caught the attention of the crew on the Nyon with his shouting, but a whistle would have done so more quickly and with far less effort. Whistles are small, light, inexpensive, reliable and hard to beat for attracting attention.

At the same time he bought the Switlik vest, Ray also purchased a pair of LAND/Shark Emergency Survival Bags, a thermal protective aid designed to combat the effects of exposure. The bag is big enough that you can completely shelter your head, even while wearing a life vest. Ray remarked, "I reckon if I had one of these LAND/Shark bags with me, I'd have been able to avoid swallowing all that sea water." He would also likely not have been as hypothermic. Since his raft had no canopy (neither does his new minimalist EAM two-person life raft), the bags would have been just as important a survival tool out of the water as in it.

On a related subject...by discarding his pants and constantly treading water, Ray likely contributed to his hypothermic condition. Heat loss in water while still is 25 times greater than in air to begin with. Heat transfer is accelerated by moving water, even more if the water is directly in contact with bare skin. Ideally, you want to lay as still as possible in the water, with your rapid heat loss areas such as groin and armpits closed down as much as possible. The HELP (Heat Escape Lessening Posture) position (for a single person) and group huddling or the "Ladder" formation (for multiple survivors) are designed to reduce heat loss from these vulnerable areas. They are potentially capable of doubling survival times compared to a person actively swimming or treading water.

The survivors' use of induced vomiting to "empty" their stomachs and mitigate the adverse effects of swallowing seawater is a unique strategy that I have not come across before. Ingesting a large volume of seawater or repeatedly vomiting swallowed seawater would each soon result in a serious free water deficit and significant dehydration. Being hypertonic, the seawater in the stomach will draw fluid out of the body and into the gut. This begins to happen immediately and as a result the contents of the stomach are somewhat diluted. Vomiting removes only a portion of what is in the stomach, not all of it. So, by inducing vomiting you would lose some of your body's free water and still retain some seawater.

The positive psychological benefits are obvious from Ray's enthusiastic comments regarding how much better he felt afterwards. The value of induced vomiting while in a weakened and exhausted condition must also be balanced by the added risk of choking and aspiration. This danger is exacerbated by the angle at which a life vest holds your head.

My medical advisors have been unable to provide a definitive answer, but most of these docs believe that, at least over the short term, Shane's advice probably caused no harm--and it left them in a better state of mind, no small matter in a survival situation. Physiologically, it may have delayed dehydration somewhat, but to my knowledge nobody has ever studied this exact scenario in any depth and the difference is unlikely to be a lot.

Shane remarked, "While it (vomiting) made us feel good, it certainly increased our dehydration...we were certainly dehydrated, I believe, we were much more dehydrated than we thought at the time, than the crew of the cutter (Kiska) thought at the time." Even a relatively minor degree of dehydration can effect your faculties and by the time you're 10% dehydrated it can have a significant effect on your judgement. Since most people go around already dehydrated to a degree, commonly about 3%-5%, it doesn't take much more to start having a negative effect. Pilots flying longer distances are often even more dehydrated as they attempt to avoid having to urinate while in flight. So, Ray and Shane probably started out with a significant deficit, one that only became worse over time and with the self-induced vomiting. Yet one more argument to be sure to have water with you at all times, just in case. Ray had made no special arrangements for water as part of his survival supplies, let alone as personal survival equipment.

Ray's account of treading water to raise his head higher in an attempt to diminish his ingestion of seawater could possibly have been be related to a design quirk of the standard double-cell aviation life vest, though it is impossible to know for sure. At the least, it is worth noting here for your enlightenment should you ever need to use one. The yoke shaped bladders meet at the front and form a vee that extends from the neck hole to the bottom of the vest. When properly donned, the lower portion of the vest is in the water and the length of the vee is angled down, away from the mouth. If there is slack in the waist belt, the body falls further away from the vest and the vest can ride completely on top of the water while the head rides lower than normal. The vee then funnels water directly to the wearer's mouth. The waist strap must be snugged up tight via the single or double adjusters provided (depending upon the model).

When I do demonstrations, virtually all novice volunteers fail to tighten the waist strap adequately. Often it is loose enough that I can easily stick my fist behind it--the long way. If it is comfortable, it is probably too loose. When wearing one of the pouch-style "helicopter" vests, or after donning a regular airline style vest for possible use at some indeterminate point later in the flight as was the case here, it is unlikely that the waist strap will be adequately tight because of the discomfort factor. Prior to the ditching, or after egressing if there is no time prior, cinch up that waist strap good and tight. When you give that seatbelt a last yank to make sure it is tight before you impact the water, do the same for your life vest waist strap.

Both survivors' necks were abraded by their life vest, Shane being in far worse shape. Any problems may have been made worse because, as we have noted in our review, the EAM vest is not gussetted, like some others, so the rough, sharp edges of the fabric are exposed. A good argument for using a gussetted life vest, such as those produced by Switlik, or in some models by Hoover. Another lesson here is that it makes good sense to wear a shirt with a collar that you can use to protect your neck by turning it up.

What about Ray's decision to continue on towards Hawaii instead of backtracking to the nearest vessel. Probably a reasonable decision, though you could argue either way. Most importantly, while not incredibly well equipped for a ditching, he did have a life raft (albeit not one I would trust with my life) and with a closing speed of approximately 410 kts., he'd meet up with the Coast Guard in no more and perhaps less time than it than it would take him to reach that ship. If he ditched before rendezvousing with the C-130, help was already on the way and probably closer than they would be otherwise. We also cannot discount that there was a good chance he might make it to shore. It's happened often enough before. With a C-130 escort, the risks of continuing were lessened, though hardly eliminated. A night ditching without power should never be taken lightly.

He could just as easily have purposely ditched in daylight upon meeting up with the C-130 as he could have upon arriving at the ship. Rescue would have probably taken a bit longer, but he would still be in excellent shape with SAR on hand. With the oil pressure continuing to drop and the oil temperature rising, both signs that inside the engine things were going from bad to worse, I would have given that option very serious consideration. Ditching during the day under power is the best possible combination, though it takes considerable will power to ditch a plane that is still soldiering on, albeit not in the best shape.

There is no doubt that Ray's sense of obligation to his client provided at least some pressure to continue on, "I'd feel pretty grim if I ended up ditching a perfectly good airplane." That is an incredibly difficult situation for someone who derives a significant portion of his income from ferrying aircraft. Luckily, it turned out okay.

While Ray tells us that the two survivors had no difficulty staying together, the observations of the Coast Guard crew convincingly contradict that. SAR crews expect survivors to try and stay together, in large part because it makes good sense, and typically, most survivors in the water try to do so. Staying together also offers SAR a larger target, the importance of which cannot be overemphasized if you are in the water with no life raft.

I have long advocated attaching a short tether to life vests to enable survivors to hang together without effort on their part. The Lifesaving Systems Corp. Pro Vest is so equipped and I have added one to my own Switlik Helicopter Crew Vest. The LAND/Shark bags that Ray purchased after this survival episode are fitted with a clip to link with other survivors. It is also possible that the two survivors would have benefited from huddling or interlocking together to conserve body heat. Even in 80 degrees F water you are going to lose body heat. Both Ray and Shane were hypothermic when rescued, Ray being the worst off.

I'm not sure what Ray expected to gain by asking the Coast Guard to notify his partner when the situation first started developing. From my point of view, I'd not want my wife to worry needlessly. While Aminta believed the information she provided to the person on the phone about Ray was being passed along, in fact none of the crews actually conducting the search received that information, which would have been of limited use in any case. Information about your survival equipment should be included in the "remarks" portion of the flight plan when filed, ensuring the SAR has that information if needed.

If Ray had made it to Hilo, or even if he ditched and was rescued promptly, he could have called Aminta up and told her about the adventure after the fact, or at least had the Coast Guard call with good news once he'd been rescued. If he ditched and hadn't been rescued by the time he was due to arrive, then it would make sense to notify her. I'd certainly pass along appropriate information at the earliest opportunity, but I would also explicitly advise them when and how I would want the contact made.

Ray's and Shane's composure during the incident appear to have been remarkably calm, under the circumstances. Certainly Ray's years of experience and self-confidence helped in this regard. His well-placed admiration of the U.S. Coast Guard also played a part in his confidence, "I knew they are the best, that they wouldn't let me down." Such a positive state of mind is always an advantage when the chips are down. He never doubted for a moment they would successfully ditch the aircraft. While he admits it was a "black moment" when the life raft was lost, he obviously didn't dwell upon it or allow it to interfere with their survival efforts. Each survivor buoyed the spirits of his co-survivor when needed. There is no substitute for such a positive attitude and support in a survival situation.

There are also a few valuable lessons the U.S. Coast Guard might take away from this incident. The most obvious being that there might likely have been an entirely different outcome but for the providential offer of Night Vision Goggles to the C-130 crew by the pilot of the Dolphin helo and Petty Officer Reese's prior experience using NVGs in the Army. There is no doubt among those on the mission that they would not have located the survivors that night if it weren't for the NVGs. Said Capt. Whorton, "I will never go on a night mission again without NVGs."

There are also a few valuable lessons the U.S. Coast Guard might take away from this incident. The most obvious being that there might likely have been an entirely different outcome but for the providential offer of Night Vision Goggles to the C-130 crew by the pilot of the Dolphin helo and Petty Officer Reese's prior experience using NVGs in the Army. There is no doubt among those on the mission that they would not have located the survivors that night if it weren't for the NVGs. Said Capt. Whorton, "I will never go on a night mission again without NVGs."

For C-130 use, it isn't necessary that the pilots be trained in NVG use or that their cockpits be retrofitted to be NVG compatible, both extremely expensive propositions. It is really only the spotters in the back that need the NVGs and that requires little or no aircraft modifications. Training the spotters in the use of NVGs is not expensive or difficult (though it is certainly possible to make it so if the wrong mindset exists--luckily, for the most part the Coast Guard has a "can do" attitude). Since there are only five Coast Guard Air Stations that fly the C-130 and only 26 active aircraft in the fleet, both the number of locations and crews needing training are relatively small. As for equipping the crews, NVGs are admittedly not inexpensive, but costs have come down at the same time that capability, ease of use, and reliability have risen. All these air stations already have NVGs for use by their helicopter crews. It would be nice, but certainly not a necessity, for the C-130s to have dedicated NVGs. I would make an educated guess that adding a modest number of NVGs to each station's complement should cover 95% of likely contingencies.

As for the cost, what is the cost in both dollars and lives of sending out C-130s on likely futile nighttime SAR missions if not NVG equipped? It wouldn't take many such sorties for the NVGs to pay for themselves.

The Flare Path

The idea of creating a "runway in the sea" using flares is not new, but it is also not a standard Coast Guard procedure. As a result, Commander Reid was left to his own initiative, for which he is to be commended, and his own devices to determine how to best get the job done and it's hard to fault his success. However, while everything worked out perfectly, at least as far as the water landing is concerned, the flares were actually dropped too close to the Archer. Ray's years of experience and flying expertise saved the day.

It shouldn't be too difficult for the Coast Guard to come up with some standard procedures for deploying flares in such a situation. It would certainly have made Reid's job easier if he could have referred to some charts or standard calculations to figure out by how much to lead the Archer. Whether he could have done any better job of it than he did under the difficult circumstances is debatable, but why not give Coast Guard pilots all the tools they might need? It's hardly likely the last time the procedure will be used.

The AMVER Contact

Shane suggested, "someone should have told them (the ship) to turn on all the lights, it would have made a big difference to us in the water, knowing it was really a ship and that they were looking for us." Indeed, it might be worthwhile to review the instructions given when an AMVER contact is made and a ship deployed to affect a rescue. It is obvious from their experience that something as simple as the ship being well lit might have been a big help and, indeed, might have been a critical difference had they been in the water much longer before the Nyon arrived.Deepwater Rescue